编者按:

据预测,到本世纪末,癌症将成为世界各国的主要死亡原因。而据中国国家癌症中心发布的统计数据,癌症已经成为中国群众健康的主要杀手。由癌症导致的死亡占据居民全部死因的第二位,占比 23.91%。

越来越多的研究表明饮食、生活方式等或会影响癌症发病率。那么,不同的食物、营养究竟与癌症有什么关系呢?哪些食物应该避免食用呢?

今天,我们特别编译 BMJ 发表的关于饮食、营养和癌症风险的文章,希望本文为诸位读者带来一定的启发和帮助。

关键信息:

●肥胖和饮酒增加了多种癌症的风险;这是造成全球范围癌症负担的最重要的营养因素。

●对于结直肠癌,加工肉会增加其患病风险,红肉可能会增加其患病风险;膳食纤维、乳制品和钙可能降低患病风险。

●含有致变物的食物可能导致癌症;某些种类的咸鱼会诱发鼻咽癌,含有黄曲霉毒素的食物会诱发肝癌。

●水果蔬菜与癌症风险之间尚未有明确的联系,尽管研究表明极低的摄入量可能会增加呼吸道、消化道相关癌症和其他癌症的风险。

●其它营养因素可能也会造成癌症风险,但是目前的论据并不足以确认这种关联。

营养与癌症

几十年来,科学家们一直怀疑营养对癌症的发生风险有重要的影响。

20 世纪 60 年代的流行病学研究就已经表明,不同地区人群之间的癌症发病率差异很大。从低风险国家移民到高风险国家的移民者的癌症发病率可能会上升到与当地人口一样的水平甚至更高1,2。这些发现暗示一些重要的致癌的环境因素的存在。

而另一些研究则表明了许多类型的癌症与饮食因素之间存在密切联系,比如肉类摄入量高的国家结直肠癌发病率高3。此外,动物实验表明,控制饮食可以改变癌症的发病率,有令人信服的证据表明,限制能量摄入可以减少癌症的发展4,5。

据预测,到本世纪末,癌症将成为世界各国的主要死亡原因6。尽管饮食因素被认为是影响患癌风险的重要因素,但是确定饮食对癌症风险的确切影响具有挑战性。在本文中,我们讨论了经确认的影响消化道相关癌症和其他类型癌症的部分饮食因素7,8,以及未来研究中面临的挑战。

BOX 1 水果和蔬菜是癌症风险的重要决定性因素吗?

早期的病例对照研究表明,摄入更多的水果蔬菜与许多类型的癌症的较低风险相关11。但随后的不受回忆和筛选偏差影响的前瞻性试验产生的结果则要弱得多。2018 年世界癌症研究基金会报道,水果和蔬菜均不被认为与任何癌症的风险有令人信服的可能的联系8。

但是也存在水果蔬菜对某些癌症具有保护作用的暗示性证据,而且有研究表明水果蔬菜摄入量低时,癌症的患病风险可能增加,这可能是因为一些水果蔬菜中的特定成分具有保护功能。

素食者既不吃肉也不吃鱼,相较于非素食者往往摄入更多的水果蔬菜。素食者(包括纯素食者和素食者)所有癌症部位的风险加起来可能比非素食主义者略低,但是在个别癌症中的结果并不明确12。

BOX 2 维生素和矿物质能降低癌症风险吗?

缺乏维生素和基本矿物质会造成身体不适,这可能包括增加对一些癌症的易感性,但是要明确这些影响是很困难的。

高剂量的维生素或矿物质补充剂在营养良好的人群中并不能够降低癌症风险,可能反而增加风险13。尽管对于健康的其他方面很重要,如叶酸的补充对于备孕的女性很重要,但维生素和矿物质补充剂不应该被用于癌症干预。

消化道相关癌症

口腔癌和咽癌

鼻咽癌在某些人群中很常见,比如中国南方的广东人,以及东南亚、北极、北非和中东的一些土著居民。

食用腌制食物与这种疾病相关,其中的机制可能与亚硝胺的形成或疱疹病毒的再激活相关10。基于病例对照研究,中式咸鱼已经被 WHO 下属的国际癌症研究机构(IARC)列为致癌物质。

总体来说,摄入更多的水果蔬菜及相关微量元素如维生素 C 和叶酸,与较低的口腔癌和咽癌风险相关(BOX1、BOX2)。但是,这些联系可能被抽烟(一种主要的非饮食风险因子7,14)、喝酒等因素所干扰,所以这些依据只能表明这些食物具有保护性作用。

食道癌

食道癌有两种类型:鳞状细胞癌和腺癌。鳞状细胞癌在世界上大多数国家占主导地位,而腺癌仅在西方国家相对常见,不过,最近发病率也在增加。

肥胖已被确定为腺癌风险因素,部分原因可能是胃内容物反流至食管造成的15,16。酒精会增加鳞状细胞癌的患病风险,但不会增加腺癌的患病风险17。吸烟会增加这两种癌症的患病风险,但对鳞状细胞癌的影响更大17。

在东非和南非的部分国家,食道癌的发病率非常高6,17。高危人群往往饮食受到诸多限制,水果、蔬菜和动物性食品的摄入量较低,因此研究人员猜测微量营养素的缺乏是导致高风险的原因(Box1 和 Box2)。

尽管有一些观察性研究和随机试验,但是多种微量营养素的相对作用尚未明确17-20。在西方国家,早期病例对照研究显示,水果和蔬菜具有保护作用21,22,但最近发表的前瞻性研究表明,两者之间的联系较弱,这可能是由于吸烟和饮酒造成的干扰16。

饮用滚烫的茶等饮料会增加食道癌的患病风险23,25,IARC 将饮用 65℃ 以上饮料列为可能的致癌因素。

胃癌

胃癌是全球第五大常见癌症,东亚地区的发病率最高6。

食用大量的腌制食品,如腌制的鱼,会增加患病风险27。这可能由于盐本身或是许多腌制食物中的亚硝酸盐产生的致癌物质导致的。盐腌食品可能会增加幽门螺旋杆菌感染的风险(已被确定为胃癌的原因28),并且可能协同促进疾病的发展29。一些证据表明,食用大量的腌菜会增加胃癌的风险,这可能是因为其中有时会存在霉菌或酵母产生的亚硝基化合物30,31。

水果蔬菜摄入较多和血液中 VC 含量较高的人,胃癌的患病风险可能会降低32。

中国林州的一项实验表明,补充 β-胡萝卜素、硒和 α-生育酚会造成胃癌致死率的显著下降18,另一些实验表明,富有维生素 C、β-胡萝卜素或两者同时服用可以增强癌前病变的消退33,34。

日本的前瞻性研究表明胃癌风险与女性饮用绿茶(大部分不吸烟)的状况呈负相关,这可能与多酚成分有关35。

这些研究表明抗氧化的微量营养素或其他抗氧化物质具有一定的保护作用,但是仍需进一步研究这种关联。

结直肠癌

结直肠癌是全球第三大常见癌症6。超重和肥胖会增加其风险8,36,37,吸烟和喝酒也会7。

研究表明,吃肉与结直肠癌发病率之间存在显著的正相关3,38。2015 年 IARC 将加工肉类列为致癌物质,将未加工的红肉列为可能致癌物质,部分原因是基于一个荟萃分析,该分析表明每天每多摄入 50g 加工肉类就会增加 17%的患病风险,每多摄入 100g 红肉则增加 18%41。最近的一些系统性综述表明,未加工的红肉造成的风险增加更小8,42。

用于保存加工肉类的化学物质,如硝酸盐和亚硝酸盐,可能会使肠道更多的暴露于会导致突变的亚硝基化合物中40。

加工和未加工的红肉都含有血红素铁,血红素铁对肠道具有细胞毒性并会增加亚硝基化合物的合成。高温烹调肉类可能会产生致突变的杂环胺和多环芳烃40。关于这些假设的机制能否揭示使用红肉和加工肉类与结直肠癌风险之间的关联,还尚不清楚39,40。

摄入较多的牛奶和钙或可降低结直肠癌风险8,43~45。钙可能通过与二级胆汁酸和血红素在肠腔内形成复合物而起到保护作用。

血液中较高的维生素 D 浓度与较低的风险相关46,但这可能受到其他如体育活动等因素干扰。孟德尔随机化基因研究表明维生素 D 并没有表现出因果关系47,48。

20 世纪 70 年代Burkitt 提出,非洲部分地区的低结肠直肠癌率是由膳食纤维的高消费引起的49。一项前瞻性研究表明,每天摄入 10 克以上的膳食纤维可使患结肠直肠癌的风险平均降低 10%;而进一步的分析表明谷类纤维和全谷类食品具有保护作用,但水果和蔬菜中的纤维则不起作用50,51。

高叶酸摄入与结直肠癌风险降低相关,这可能是因为适度的叶酸浓度维持了基因组的稳定性8,但是有研究表明较高的叶酸水平可能会促进直肠肿瘤的生长52。

叶酸对于结直肠癌的风险是否存在实质性影响尚无定论。大多数补充叶酸的随机试验都表明没有影响53,54,尽管对亚甲基四氢叶酸还原酶基因的研究表明,较低的血液叶酸水平与风险轻微降低相关,但这些数据并不能直接解释原因55。

非消化道癌症

肝癌

酒精是肝癌的主要饮食相关风险因素,机制可能涉及到肝硬化和酒精性肝炎的发生7。超重和肥胖同样增加了风险8。

黄曲霉毒素是湿热条件下贮存的谷物、坚果、干果等食物中的黄曲霉菌产生的一种致突变物质,被 IARC 列为致癌物质,也是一些低收入国家(该地区人群易患有肝炎病毒感染)的重要风险因素56。

主要的非饮食风险因素是慢性乙型或丙型肝炎病毒感染。

一些研究显示,喝咖啡与肝癌风险之间存在负相关。咖啡可能确实具有保护作用,因为其中含有很多生物活性物质57,58,但是这种关联性可能受到了残余混杂的影响,也可能会受到由于处于亚临床状态导致饮用咖啡欲望减少的影响。

胰腺癌

肥胖大约增加了 20%的胰腺癌风险8。糖尿病也与该疾病的风险增加相关,孟德尔随机效应分析表明,这是由于胰岛素升高所致,而非糖尿病本身59。目前,关于饮食组分和该癌症的患病风险的研究结果并不一致8。

肺癌

肺癌是全球发病率最高的癌症,大量吸烟会使患病风险增加 40 倍6,7。

前瞻性研究表明,高果蔬摄入量与吸烟者胃癌风险的轻微下降有关,但在不吸烟者中无关60,61。果蔬与吸烟者肺癌风险的轻微负相关,可能表明了其存在保护作用,但是这也可能是因为吸烟造成的残余混杂的影响(BOX 1)。

有研究测试了 Β-胡萝卜素(其中一个使用了维生素 A)来预防肺癌,结果却发现干预组的志愿者具有更高的肺癌风险13,62。

乳腺癌

乳腺癌是全球第二大癌症6。生殖和激素是风险的决定性因素63。肥胖可能通过增加脂肪组织中芳香化酶产生的雌激素增加绝经后女性的乳腺癌风险64。大部分研究表明,绝经前女性的肥胖与风险降低有关,这可能是因为不排卵频率增加造成的雌激素水平下降65。

还有研究表明,每天多喝一杯酒会相应增加 10%的风险8,66,其中的机制可能与雌激素的增加有关。

关于高脂肪摄入量会增加成人乳腺癌风险的论点存在争议。早前的病例对照研究支持这种假设,但是前瞻性观察研究8和另外两个减脂饮食的随机对照实验发现并非如此67,68。

对于其他如肉类、乳制品和水果等饮食因素的研究结果整体上也不一致8。近期的一些研究表明,蔬菜摄入量与雌激素受体阴性乳腺癌呈负相关8,69,70,膳食纤维与整体风险呈负相关8,71。异黄酮,大部分来源于大豆,与亚洲人乳腺癌风险较低相关72。这种潜在联系具有重要意义,应当研究其中因果关系。

前列腺癌

前列腺癌是全球第四大常见癌症6,被确认的风险因素仅有年龄、家族史,黑人种族和遗传因素73。肥胖可能会增加侵袭性前列腺癌的风险8。

主要来源于番茄的番茄红素与前列腺癌的患病风险降低相关,但是相关数据尚不明朗8。

一些研究表明,其他微量营养素的较高水平,如 Β-胡萝卜素、维生素 D、维生素 E 和硒,能够降低风险,但是试验和孟德尔随机效应分析并未得出一致性结论47,74~76。

主要来源于豆制品的异黄酮被证实与亚洲男性患前列腺癌的风险降低相关77。而在日本,血液中异黄酮水平与日本男性的前列腺癌风险却呈负相关78。

大量证据表明,刺激细胞分化的激素胰岛素样生长因子-1 的高水平会增加前列腺癌的风险,不过仍然需要进一步研究确定饮食因素如动物蛋白是否会通过影响这种激素的形成,从而改变前列腺癌的患病风险79。

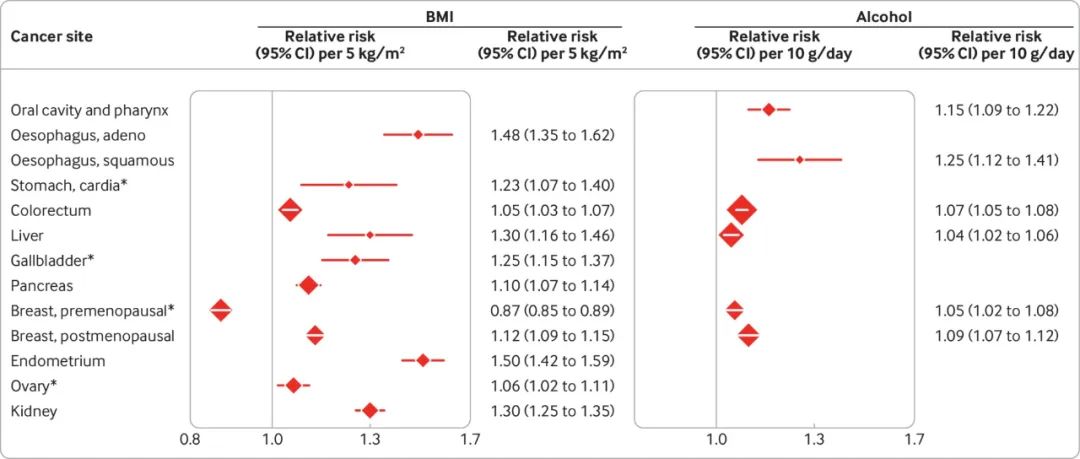

图 1. BMI、酒精和癌症风险

专家组的评估

世界各国饮食存在巨大差异,而饮食可能对许多癌症都有影响,那么,我们怎么知道应该避免哪种食物或饮食方式呢?

世界癌症研究基金会(WCRF)和 IARC 通过系统性回顾现有论据和专家组评估,综述了食物和营养素的致癌风险。尽管和许多营养研究一样,这个方向也十分复杂,但是 WCRF 和 IARC 确认了某些可能与癌症风险相关的营养因素。

WCRF 和 IARC 表示肥胖和酒精可能会造成多个部位的癌变(图 1)。

无论是超重还是肥胖,体重指数(BMI)每增加 5kg/m2,癌症风险会增加,从结直肠癌风险增加 5%到子宫内膜癌风险增加 50%80。

对于酒精,每天多摄入 10g 造成的风险增加从肝癌的4%到食道鳞状细胞癌的 25%不等。

加工肉被 WCRF 和 IARC 认定为是一个可信的致癌原因:最近 WCRF 报告了每天增加 50g 加工肉的直肠癌相对风险为 1.16(1.08-1.26)8。

IARC 认为中式咸鱼是一种致癌物质,每周多吃一份造成的鼻咽癌相对风险为1.31(1.16-1.47)8,10。此外,被黄曲霉素污染的食物也被认为是致癌物质56。

目前,没有一个专家团体认有饮食因素具有令人信服的预防癌症的作用。

表 1. 营养与癌症之间的可能联系

不确定性仍然存在

WCRF 和 IARC 认为营养因素与癌症风险之间“可能”具有因果关系或存在保护作用(表 1)。一些研究人员可能认为,“可能”的标准不够严格。因此,当使用这些报告来预估饮食的可能影响或是做出膳食建议时,必须记住这一点,进一步的证据可能会改变这些结论。

值得注意的是,WCRF 也将成人和青年期的体脂列为预防绝经前乳腺癌发生的因素。新的证据65让我们认同其中的关联,所以将这种关联放在图 1 而非表 1 中。

肥胖可能会增加口腔癌、咽癌和侵袭性前列腺癌的风险。

喝酒可能会增加胃癌的风险,但是与肾癌的风险呈负相关,这可能表明确实存在生理学效应或是出现残余混杂或偏倚81。

温度过高的热饮品可能增加食道癌的风险,腌制食物可能会增加胃癌的风险,而一些膳食因素可能会降低直肠癌的风险。

专家组还总结道,子宫内膜癌的风险可能因高血糖负荷饮食而增加。咖啡被认为可能对肝癌和子宫内膜癌有保护作用,但是现有的一些学者认为这种结论可能并不准确,关于咖啡和子宫内膜癌的数据可能受到只包含部分论据的选择性文献所影响82。

除了超重和肥胖,成人身高过高也与一些癌症的风险相关(BOX 3)。

丙烯胺酸,一种在高温烹调和许多高碳水化合物(如薯片、麦片脆和咖啡)加工过程中产生的化学物质,被 IARC 列为可能致癌物质85。

这一结论主要是基于实验动物中的研究,大部分流行病学研究的结果则为无效或无结论86,但是这可能受到难以对长期接触效果进行评估,以及受吸烟影响的限制。近来关于这种化学物质的可能的突变标志研究表明,它可能会确实会造成风险87。

BOX 3 为什么个子更高的人癌症风险较高?

大部分癌症的风险都会随身高增加。WCRF 的一项系统性综述表明,每长高 5cm 癌症风险的增加从前列腺癌的 4%到恶性黑色素瘤的 12%不等83。其中机制尚不明确,但是更高的人拥有更多具有癌症风险的干细胞,或是像胰岛素样生长因子-1 这样同时影响身高和癌症风险的因素84。

营养不良造成生长受限,而在儿童时期和青少年时期,给予充足的营养,比如能量和蛋白质的充分摄入,可能导致相对较高的身高和整体较高的癌症风险83。但是,尚不清楚更好地了解这一通路能否带来降低癌症风险的方法。

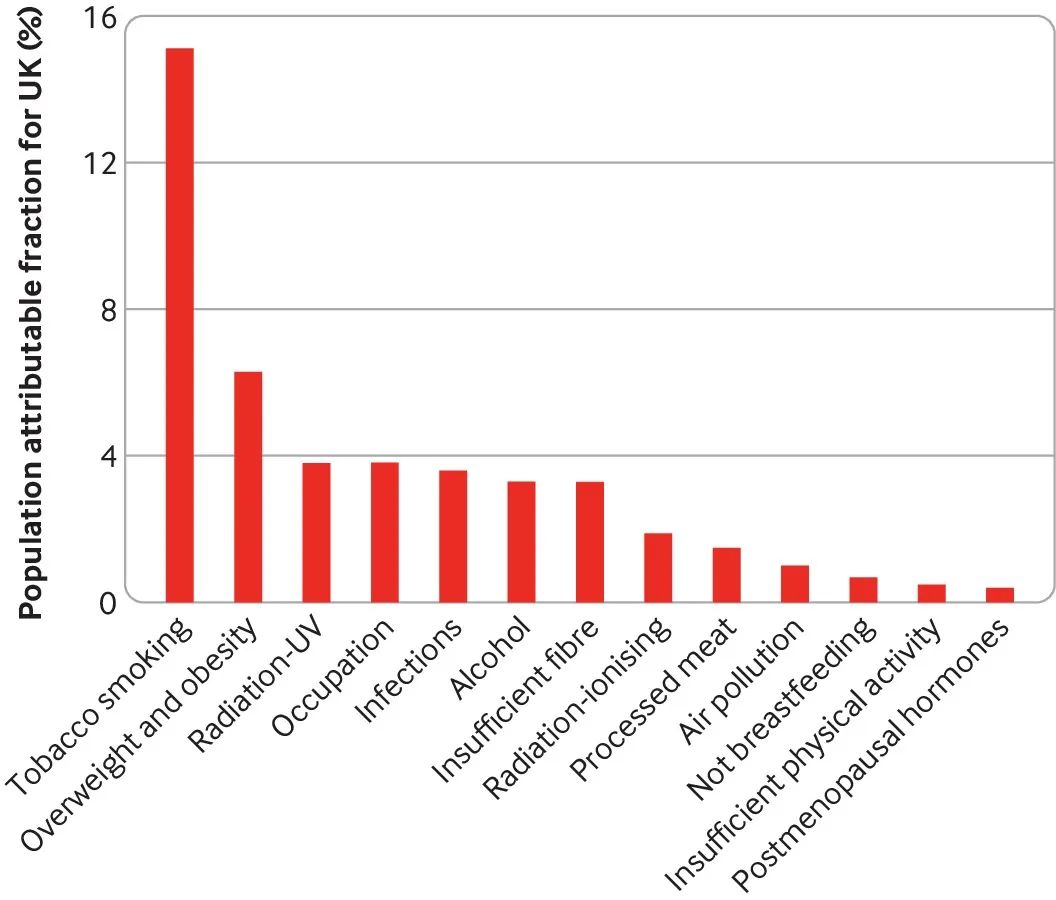

图 2.英国癌症与不同因素间的联系

膳食作为预防癌症的因素有多重要?

图 2 显示了可调整风险因素(包括饮食因素)在英国癌症病例中所占比例的最新预估,WCRF 和 IARC 将饮食因素列为经论证的致癌原因88。超重和肥胖是第二大归因,占英国癌症的 6.3%,但是是非吸烟者患癌的第一大原因。

饮酒(3.3%)、膳食纤维(3.3%)和加工肉类(1.5%)也在十大原因之中(尽管膳食纤维目前被 WCFR 列为“可能”原因)。

其他国家的分析也得出了类似的预估状况,巴西的预估为:超重和肥胖占 4.9%,饮酒占 3.8%,膳食纤维占 0.8%,加工肉类占 0.6%89。然而,在肥胖发生率较低的日本,超重和肥胖占 1.1%,饮酒占 6.3%(盐占 1.6%)90。

未来方向

研究营养对健康的影响是困难的91。我们在本文中总结了营养与癌症之间的几个相对明确的联系,但是未来的研究可能会揭示出更多重要的风险因素——可能是特定的食物成分或是饮食模式,比如植物基饮食。

未来,新一代的研究需要加强对长期暴露的相关评估,如重复的饮食记录(现在可以使用在线调查问卷)等92。

饮食摄入与营养水平的生物标志物可能会被更广泛地使用,而且也会通过如代谢组学等方法发现新的生物标志物,但是它们需要根据可能的混杂或反向因果关系进行验证并做出阐释。

对于膳食摄入和营养水平中的某些暴露情况,孟德尔随机效应可以帮助理清因果关系93,但是仍需要随机试验来验证具体的假设。

尝试调动全球可获得的数据进行系统性分析,对于减少偏倚带来的风险也很重要94。

对于公共健康和政策,最首要的应该是处理已知的饮食相关的癌症风险因素,特别是肥胖和酒精。

参考文献:

(滑动下方文字查看)

1.Haenszel W, Kurihara M. Studies of Japanese migrants. I. Mortality from cancer and other diseases among Japanese in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst 1968;40:43-68.5635018

2.Shimizu H, Mack TM, Ross RK, Henderson BE. Cancer of the gastrointestinal tract among Japanese and white immigrants in Los Angeles County. J Natl Cancer Inst 1987;78:223-8.3468285

3.Armstrong B, Doll R. Environmental factors and cancer incidence and mortality in different countries, with special reference to dietary practices. Int J Cancer 1975;15:617-31. 10.1002/ijc.2910150411 1140864

4.Moreschi C. Beziehungen zwischen Ernährung und Tumorwachstum. Ztschr f Immunitätsforsch. 1909;2:651.

5.McCay CM, Pope F, Lunsford W. Experimental prolongation of the life span. Bull N Y Acad Med 1956;32:91-101.13284491

6.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394-424. 10.3322/caac.21492 30207593

7.Swerdlow AJ, Doll RS, Peto R. Epidemiology of cancer. In: Warrell DA, Cox TM, Firth JD, eds. Oxford Textbook of Medicine. 5th ed. Oxford University Press, 2010: 193-21810.1093/med/9780199204854.003.0601 .

8.World Cancer Research Fund, American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, nutrition, physical activity and cancer: a global perspective. Continuous update project expert report 2018. https://www.wcrf.org/dietandcancer.

9.Chang ET, Adami HO. Nasopharyngeal cancer. In: Adami H-O, Hunter DJ, Lagiou P, Mucci L. Textbook of Cancer Epidemiology, Third edition. Eds, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2018:159-181.

10.Secretan B, Straif K, Baan R, etal. WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. A review of human carcinogens—Part E: tobacco, areca nut, alcohol, coal smoke, and salted fish. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:1033-4. 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70326-2 19891056

11.World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. AICR, 2007.

12.Appleby PN, Key TJ. The long-term health of vegetarians and vegans. Proc Nutr Soc 2016;75:287-93. . 10.1017/S0029665115004334 26707634

13.Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta Carotene Cancer Prevention Study Group. The effect of vitamin E and beta carotene on the incidence of lung cancer and other cancers in male smokers. N Engl J Med 1994;330:1029-35. 10.1056/NEJM199404143301501 8127329

14.Rider JR, Brennan P, Lagiou P. Oral and pharyngeal cancer. In: Adami H-O, Hunter DJ, Lagiou P, Mucci L, eds. Textbook of Cancer Epidemiology, 3rd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2018:137-157.

15.Reeves GK, Pirie K, Beral V, Green J, Spencer E, Bull DMillion Women Study Collaboration. Cancer incidence and mortality in relation to body mass index in the Million Women Study: cohort study. BMJ 2007; 335:1134.10.1136/bmj.39367.495995.AE 17986716

16.Vingeliene S, Chan DSM, Vieira AR, etal . An update of the WCRF/AICR systematic literature review and meta-analysis on dietary and anthropometric factors and esophageal cancer risk. Ann Oncol 2017;28:2409-19. 10.1093/annonc/mdx338 28666313

17.Abnet CC, Nyrén O, Adami HO. Esophageal cancer. In: Adami H-O, Hunter DJ, Lagiou P, Mucci L, eds. Textbook of Cancer Epidemiology, 3rd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2018:183-211.

18.Blot WJ, Li JY, Taylor PR, etal . Nutrition intervention trials in Linxian, China: supplementation with specific vitamin/mineral combinations, cancer incidence, and disease-specific mortality in the general population. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:1483-92. 10.1093/jnci/85.18.1483 8360931

19.Hashemian M, Poustchi H, Abnet CC, etal . Dietary intake of minerals and risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: results from the Golestan Cohort Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;102:102-8. 10.3945/ajcn.115.107847 26016858

20.Hashemian M, Murphy G, Etemadi A, etal . Toenail mineral concentration and risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, results from the Golestan Cohort Study. Cancer Med 2017;6:3052-9. 10.1002/cam4.1247 29125237

21.Cheng KK, Sharp L, McKinney PA, etal . A case-control study of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in women: a preventable disease. Br J Cancer 2000;83:127-32. 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1121 10883680

22.Terry P, Lagergren J, Hansen H, Wolk A, Nyrén O. Fruit and vegetable consumption in the prevention of oesophageal and cardia cancers. Eur J Cancer Prev 2001;10:365-9. 10.1097/00008469-200108000-00010 11535879

23.Lubin JH, De Stefani E, Abnet CC, etal . Maté drinking and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in South America: pooled results from two large multicenter case-control studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2014;23:107-16. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0796 24130226

24.Chen Y, Tong Y, Yang C, etal . Consumption of hot beverages and foods and the risk of esophageal cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. BMC Cancer 2015;15:449. 10.1186/s12885-015-1185-1 26031666

25.Yu C, Tang H, Guo Y, etal. China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group. Hot tea consumption and its interactions with alcohol and tobacco use on the risk for esophageal cancer: A population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2018;168:489-97. 10.7326/M17-2000 29404576

26.Loomis D, Guyton KZ, Grosse Y, etal. International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. Carcinogenicity of drinking coffee, mate, and very hot beverages. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:877-8. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30239-X 27318851

27.Takachi R, Inoue M, Shimazu T, etal. Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study Group. Consumption of sodium and salted foods in relation to cancer and cardiovascular disease: the Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;91:456-64. 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28587 20016010

28.Fox JG, Dangler CA, Taylor NS, King A, Koh TJ, Wang TC. High-salt diet induces gastric epithelial hyperplasia and parietal cell loss, and enhances Helicobacter pylori colonization in C57BL/6 mice. Cancer Res 1999;59:4823-8.10519391

29.Nozaki K, Shimizu N, Inada K, etal . Synergistic promoting effects of Helicobacter pylori infection and high-salt diet on gastric carcinogenesis in Mongolian gerbils. Jpn J Cancer Res 2002;93:1083-9. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2002.tb01209.x 12417037

30.Tsugane S. Salt, salted food intake, and risk of gastric cancer: epidemiologic evidence. Cancer Sci 2005;96:1-6. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00006.x 15649247

31.Ye W, Nyrén O, Adami HO. Stomach cancer. In: Adami H-O, Hunter DJ, Lagiou P, Mucci L, eds. Textbook of Cancer Epidemiology, 3rd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2018:213-241.

32.Lam TK, Freedman ND, Fan JH, etal . Prediagnostic plasma vitamin C and risk of gastric adenocarcinoma and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in a Chinese population. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;98:1289-97. 10.3945/ajcn.113.061267 24025629

33.Correa P, Fontham ET, Bravo JC, etal . Chemoprevention of gastric dysplasia: randomized trial of antioxidant supplements and anti-helicobacter pylori therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:1881-8. 10.1093/jnci/92.23.1881 11106679

34.Plummer M, Vivas J, Lopez G, etal . Chemoprevention of precancerous gastric lesions with antioxidant vitamin supplementation: a randomized trial in a high-risk population. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007;99:137-46. 10.1093/jnci/djk017 17227997

35.Inoue M, Sasazuki S, Wakai K, etal. Research Group for the Development and Evaluation of Cancer Prevention Strategies in Japan. Green tea consumption and gastric cancer in Japanese: a pooled analysis of six cohort studies. Gut 2009;58:1323-32. 10.1136/gut.2008.166710 19505880

36.Pischon T, Lahmann PH, Boeing H, etal . Body size and risk of colon and rectal cancer in the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). J Natl Cancer Inst 2006;98:920-31. 10.1093/jnci/djj246 16818856

37.Kyrgiou M, Kalliala I, Markozannes G, etal . Adiposity and cancer at major anatomical sites: umbrella review of the literature. BMJ 2017;356:j477. 10.1136/bmj.j477 28246088

38.Kono S. Secular trend of colon cancer incidence and mortality in relation to fat and meat intake in Japan. Eur J Cancer Prev 2004;13:127-32. 10.1097/00008469-200404000-00006 15100579

39.Bouvard V, Loomis D, Guyton KZ, etal. International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. Carcinogenicity of consumption of red and processed meat. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:1599-600. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00444-1 26514947

40.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Red meat and processed meat. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic risks to Humans. Vol 114. IARC, 2018.

41.Chan DS, Lau R, Aune D, etal . Red and processed meat and colorectal cancer incidence: meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS One 2011;6:e20456. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020456 21674008

42.Schwingshackl L, Schwedhelm C, Hoffmann G, etal . Food groups and risk of colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer 2018;142:1748-58. 10.1002/ijc.31198 29210053

43.Cho E, Smith-Warner SA, Spiegelman D, etal . Dairy foods, calcium, and colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of 10 cohort studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96:1015-22. 10.1093/jnci/djh185 15240785

44.Murphy N, Norat T, Ferrari P, etal . Consumption of dairy products and colorectal cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and and Nutrition (EPIC). PLoS One 2013;8:e72715. 10.1371/journal.pone.0072715 24023767

45.Zhang X, Keum N, Wu K, etal . Calcium intake and colorectal cancer risk: Results from the nurses’ health study and health professionals follow-up study. Int J Cancer 2016;139:2232-42. 10.1002/ijc.30293 27466215

46.McCullough ML, Zoltick ES, Weinstein SJ, etal . Circulating vitamin D and colorectal cancer risk: an international pooling project of 17 cohorts. J Natl Cancer Inst 2018. 10.1093/jnci/djy087. 29912394

47.Dimitrakopoulou VI, Tsilidis KK, Haycock PC, etal. GECCO ConsortiumPRACTICAL ConsortiumGAME-ON Network (CORECT, DRIVE, ELLIPSE, FOCI-OCAC, TRICL-ILCCO). Circulating vitamin D concentration and risk of seven cancers: Mendelian randomisation study. BMJ 2017;359:j4761. 10.1136/bmj.j4761 29089348

48.He Y, Timofeeva M, Farrington SM, etal. SUNLIGHT consortium. Exploring causality in the association between circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D and colorectal cancer risk: a large Mendelian randomisation study. BMC Med 2018;16:142. 10.1186/s12916-018-1119-2 30103784

49.Burkitt DP. Editorial: Large-bowel cancer: an epidemiologic jigsaw puzzle. J Natl Cancer Inst 1975;54:3-6. 10.1093/jnci/54.1.3 1113310

50.Aune D, Chan DS, Lau R, etal . Dietary fibre, whole grains, and risk of colorectal cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ 2011;343:d6617. 10.1136/bmj.d6617 22074852

51.Reynolds A, Mann J, Cummings J, Winter N, Mete E, Te Morenga L. Carbohydrate quality and human health: a series of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Lancet 2019;393:434-45. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31809-9 30638909

52.Kim YI. Folate: a magic bullet or a double edged sword for colorectal cancer prevention?Gut 2006;55:1387-9. 10.1136/gut.2006.095463 16966698

53.Vollset SE, Clarke R, Lewington S, etal. B-Vitamin Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Effects of folic acid supplementation on overall and site-specific cancer incidence during the randomised trials: meta-analyses of data on 50,000 individuals. Lancet 2013;381:1029-36. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62001-7 23352552

54.Oliai Araghi S, Kiefte-de Jong JC, Dijk SCV, etal . Folic acid and vitamin-B12 supplementation and the risk of cancer: long-term follow-up of the B-vitamins for the Prevention Of Osteoporotic Fractures (B-PROOF) trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2018. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-1198. 30341095

55.Kennedy DA, Stern SJ, Matok I, etal . Folate intake, MTHFR polymorphisms, and the risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Epidemiol 2012;2012:952508. 10.1155/2012/952508 23125859

56.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Aflatoxins. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Vol 100F. IARC, 2012.

57.Aleksandrova K, Bamia C, Drogan D, etal . The association of coffee intake with liver cancer risk is mediated by biomarkers of inflammation and hepatocellular injury: data from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;102:1498-508. 10.3945/ajcn.115.116095 26561631

58.Bamia C, Stuver S, Mucci L. Cancer of the liver and biliary tract. In: Adami H-O, Hunter DJ, Lagiou P, Mucci L, eds. Textbook of Cancer Epidemiology, 3rd ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2018:277-307.

59.Carreras-Torres R, Johansson M, Gaborieau V, etal . The role of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic factors in pancreatic cancer: a mendelian randomization study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017;109. 10.1093/jnci/djx012 28954281

60.Vieira AR, Abar L, Vingeliene S, etal . Fruits, vegetables and lung cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol 2016;27:81-96. 10.1093/annonc/mdv381 26371287

61.Pirie K, Peto R, Green J, Reeves GK, Beral VMillion Women Study Collaborators. Lung cancer in never smokers in the UK Million Women Study. Int J Cancer 2016;139:347-54. 10.1002/ijc.30084 26954623

62.Omenn GS, Goodman GE, Thornquist MD, etal . Effects of a combination of beta carotene and vitamin A on lung cancer and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 1996;334:1150-5. 10.1056/NEJM199605023341802 8602180

63.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and breastfeeding: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 50302 women with breast cancer and 96973 women without the disease. Lancet 2002;360:187-95. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09454-0 12133652

64.Grodin JM, Siiteri PK, MacDonald PC. Source of estrogen production in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1973;36:207-14. 10.1210/jcem-36-2-207 4688315

65.Schoemaker MJ, Nichols HB, Wright LB, etal. Premenopausal Breast Cancer Collaborative Group. Association of body mass index and age with subsequent breast cancer risk in premenopausal women. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:e181771. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1771 29931120

66.Allen NE, Beral V, Casabonne D, etal. Million Women Study Collaborators. Moderate alcohol intake and cancer incidence in women. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009;101:296-305. 10.1093/jnci/djn514 19244173

67.Prentice RL, Caan B, Chlebowski RT, etal . Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of invasive breast cancer: the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial. JAMA 2006;295:629-42. 10.1001/jama.295.6.629 16467232

68.Martin LJ, Li Q, Melnichouk O, etal . A randomized trial of dietary intervention for breast cancer prevention. Cancer Res 2011;71:123-33.10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1436 21199800

69.Farvid MS, Chen WY, Rosner BA, etal . Fruit and vegetable consumption and breast cancer incidence: Repeated measures over 30 years of follow-up. Int J Cancer 2018. 10.1002/ijc.31653. 29978479

70.Jung S, Spiegelman D, Baglietto L, etal . Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of breast cancer by hormone receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013;105:219-36. 10.1093/jnci/djs635 23349252

71.Key TJ, Balkwill A, Bradbury KE, etal . Foods, macronutrients and breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women: a large UK cohort. Int J Epidemiol 2019;48:489-500. 10.1093/ije/dyy238 30412247

72.Dong JY, Qin LQ. Soy isoflavones consumption and risk of breast cancer incidence or recurrence: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011;125:315-23. . 10.1007/s10549-010-1270-8 21113655

73.Price AJ, Key TJ. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. In: Hamdy FC, Eardley I, eds. Oxford Textbook of Urological Surgery. 1st ed. Oxford University Press, 2017.

74.Lippman SM, Klein EA, Goodman PJ, etal . Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of prostate cancer and other cancers: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA 2009;301:39-51. 10.1001/jama.2008.864 19066370

75.Gaziano JM, Glynn RJ, Christen WG, etal . Vitamins E and C in the prevention of prostate and total cancer in men: the Physicians’ Health Study II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;301:52-62. 10.1001/jama.2008.862 19066368

76.Heinonen OP, Albanes D, Virtamo J, etal . Prostate cancer and supplementation with alpha-tocopherol and beta-carotene: incidence and mortality in a controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998;90:440-6. 10.1093/jnci/90.6.440 9521168

77.Yan L, Spitznagel EL. Soy consumption and prostate cancer risk in men: a revisit of a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89:1155-63. 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27029 19211820

78.Perez-Cornago A, Appleby PN, Boeing H, etal . Circulating isoflavone and lignan concentrations and prostate cancer risk: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from seven prospective studies including 2,828 cases and 5,593 controls. Int J Cancer 2018;143:2677-86. 10.1002/ijc.31640 29971774

79.Travis RC, Appleby PN, Martin RM, etal . A meta-analysis of individual participant data reveals an association between circulating levels of IGF-I and prostate cancer risk. Cancer Res 2016;76:2288-300. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1551 26921328

80.Lauby-Secretan B, Scoccianti C, Loomis D, Grosse Y, Bianchini F, Straif KInternational Agency for Research on Cancer Handbook Working Group. Body fatness and cancer–viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med 2016;375:794-8. 10.1056/NEJMsr1606602 27557308

81.Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, etal . Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: a comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 2015;112:580-93. 10.1038/bjc.2014.579 25422909

82.Yang TO, Crowe F, Cairns BJ, Reeves GK, Beral V. Tea and coffee and risk of endometrial cancer: cohort study and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;101:570-8. 10.3945/ajcn.113.081836 25733642

83.World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Height and birthweight and the risk of cancer. Available at: https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/ Height-and-birthweight_0.pdf. 2018.

84.Giovannucci E. A growing link-what is the role of height in cancer risk?Br J Cancer 2019;120:575-6. 10.1038/s41416-018-0370-9 30778142

85.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Acrylamide. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. IARC, 1994.

86.Pelucchi C, Bosetti C, Galeone C, La Vecchia C. Dietary acrylamide and cancer risk: an updated meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 2015;136:2912-22. 10.1002/ijc.29339 25403648

87.Zhivagui M, Ng AWT, Ardin M, etal . Experimental and pan-cancer genome analyses reveal widespread contribution of acrylamide exposure to carcinogenesis in humans. Genome Res 2019;29:521-31. 10.1101/gr.242453.118 30846532

88.Brown KF, Rumgay H, Dunlop C, etal . The fraction of cancer attributable to modifiable risk factors in England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland, and the United Kingdom in 2015. Br J Cancer 2018;118:1130-41. 10.1038/s41416-018-0029-6 29567982

89.Rezende LFM, Lee DH, Louzada MLDC, Song M, Giovannucci E, Eluf-Neto J. Proportion of cancer cases and deaths attributable to lifestyle risk factors in Brazil. Cancer Epidemiol 2019;59:148-57. 10.1016/j.canep.2019.01.021 30772701

90.Inoue M, Sawada N, Matsuda T, etal . Attributable causes of cancer in Japan in 2005—systematic assessment to estimate current burden of cancer attributable to known preventable risk factors in Japan. Ann Oncol 2012;23:1362-9.10.1093/annonc/mdr437 22048150

91.Mozaffarian D, Rosenberg I, Uauy R. History of modern nutrition science—implications for current research, dietary guidelines, and food policy. BMJ 2018;361:k2392. 10.1136/bmj.k2392 29899124

92.Liu B, Young H, Crowe FL, etal . Development and evaluation of the Oxford WebQ, a low-cost, web-based method for assessment of previous 24 h dietary intakes in large-scale prospective studies. Public Health Nutr 2011;14:1998-2005. 10.1017/S1368980011000942 21729481

93.Pierce BL, Kraft P, Zhang C. Mendelian randomization studies of cancer risk: a literature review. Curr Epidemiol Rep 2018;5:184-96. 10.1007/s40471-018-0144-1 30034993

94.Ioannidis JPA. The challenge of reforming nutritional epidemiologic research. JAMA 2018;320:969-70. 10.1001/jama.2018.11025 30422271

原文链接:Key T J, Bradbury K E, Perezcornago A, et al. Diet, nutrition, and cancer risk: what do we know and what is the way forward?[J]. BMJ, 2020.

作者|Timothy J Key,Kathryn E Bradbury,Aurora Perez-Cornago,Rashmi Sinha,Konstantinos K Tsilidis 和 Shoichiro Tsugane

编译|C。

审校|617